22.07.2025. » 08:35

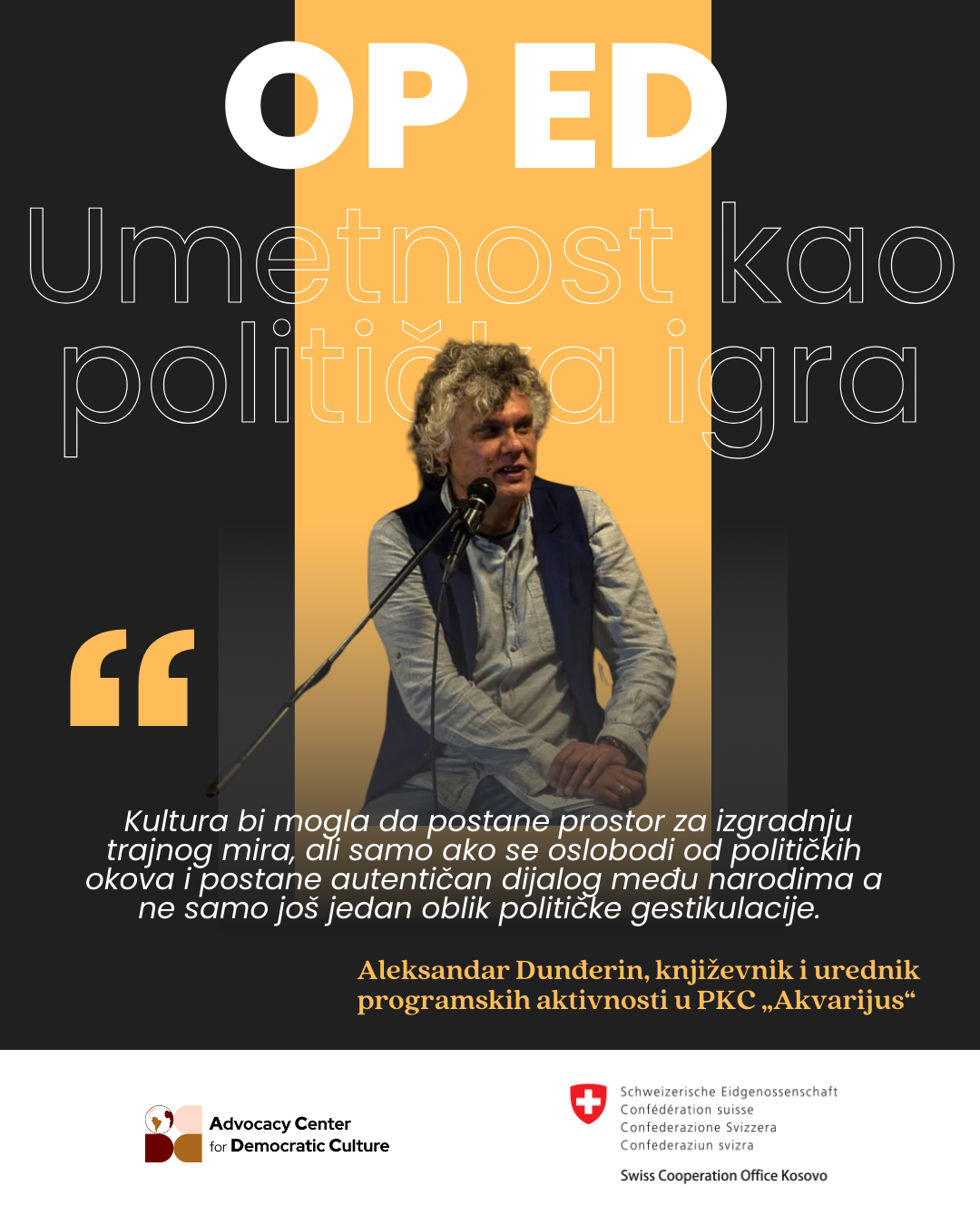

Tamo gde se susreću duše stvaralaca

Na mestu gde se dodiruju horizonti, umetnici...

13.05.2025. » 20:28

Iskustvo na omladinskim kampovima - Nezaboravno iskustvo koje bih rado ponovio

U periodu od februara do maja 2025....

26.04.2025. » 08:24

Otkrivanje zajedništva kroz iskustva sa omladinskog kmapa

Svako novo poznanstvo je priča za sebe....

22.04.2025. » 09:19

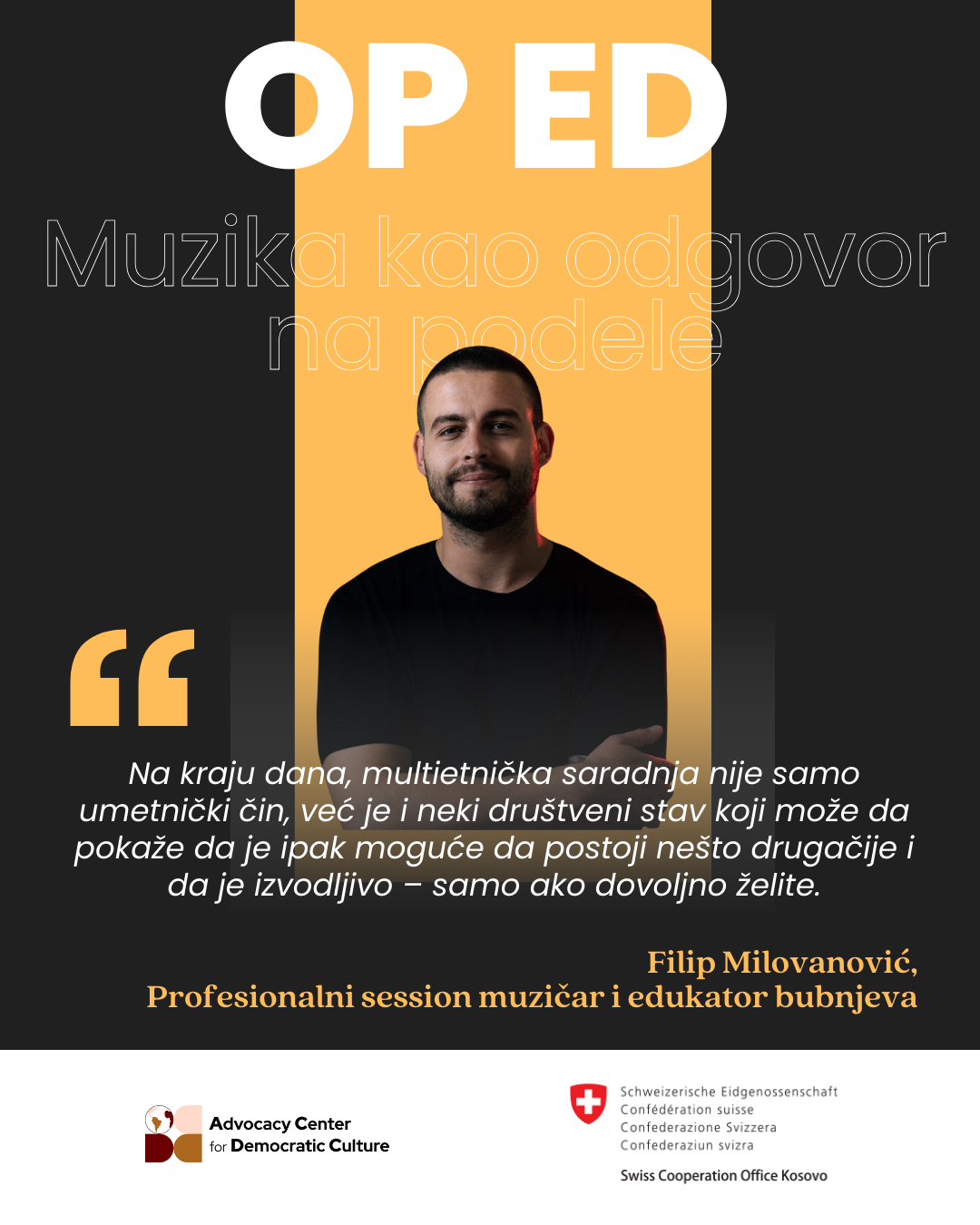

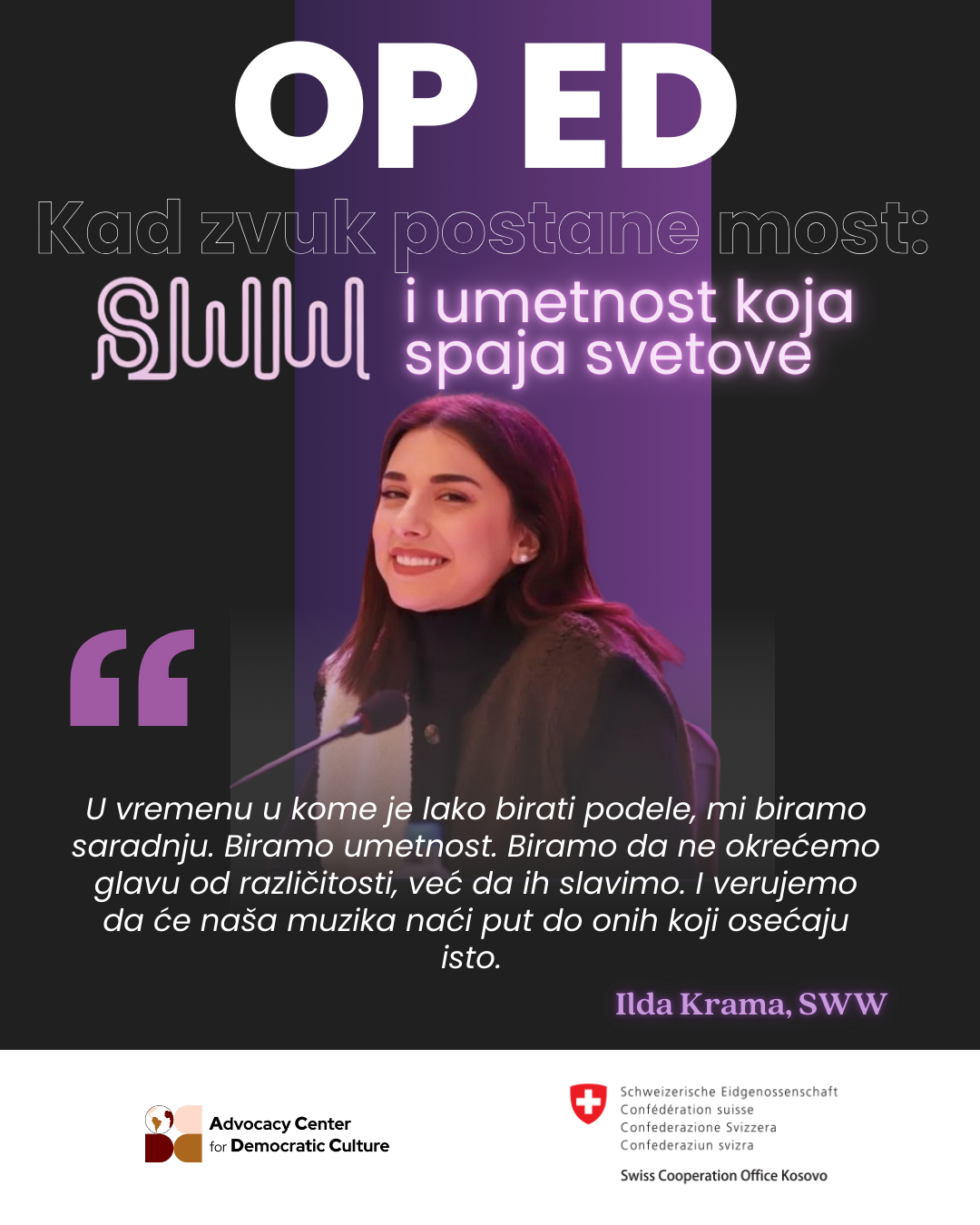

Kad zvuk postane most: SWW i umetnost koja spaja svetove

Na mestima gde drugi vide samo granice,...